Overview:

A Brooklyn parent’s quiet protest against her daughter’s public school uniform policy reveals the broader inequities, outdated justifications, and disproportionate impact of dress codes—especially on students of color, low-income communities, and marginalized identities—highlighting the urgent need for inclusive reform.

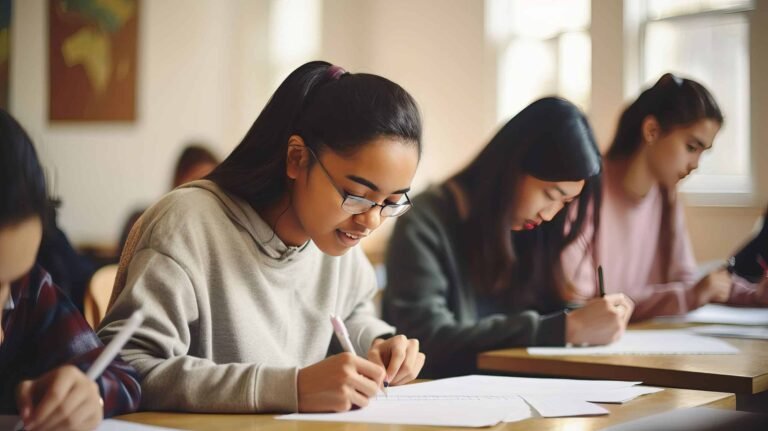

At the start of the 2024-2025 school year, in a passive protest to my preschooler’s uniform policy at her public elementary school in Brooklyn, I bought slate blue pants instead of the required navy blue. I understood the risks, but I did not care. My favorite online clothing outlet for children was having a sale on bamboo pants that would surely not irritate my daughter’s eczema-prone skin like the school-recommended uniform company’s synthetic fabrics. Would the school penalize my 4-year-old daughter or call me out over Zoom at the monthly PTA meeting? I waited for a note, an email, or a text. Nothing came.

Meanwhile my daughter’s principal continued haranguing the entire school over the Remind app. She reminded us …

- That the school’s uniform policy called for navy blue bottoms

- Students must wear school house T-shirts or white polo shirts

In the winter, girls could wear black stockings under their skirts but no other colors.

In New York, where I live with my partner and daughter, each school (in other words, the principal) has the authority to develop and enforce a dress code policy — albeit it needs to adhere to the City Council and Department of Education’s policies. The uniform code must also be “gender-neutral and applied uniformly.”

Months prior to the start of the school year, we spent hundreds buying a new wardrobe for my preschooler that included white polo tops (stained early in the year by non-washable paint), house T-shirts, and blue bottoms. It hardly felt more economical, particularly in the short term. And, by the second-to-the-last day of school, most of the tops we bought at the school store, especially the white polo shirts, were in ruins and/or faded so badly that they will likely never see another school year. The poor quality uniforms were no match for a preschooler. Try to object to the uniform policy at a public school in New York or — anywhere in the country that mandates such measures — and you will hear the same cries from administrators, teachers, and parents alike:

Uniforms balance the playing field

- Uniforms increase school spirit

- Uniforms boost attendance

- Uniforms prevent bullying and improve school safety

- Uniforms save money

- Uniforms provide a sense of equality and unity

The problem with those arguments: research that supports such claims is outdated and limited, according to the study School Uniforms and Student Behavior: Is There a Link? which was published in the Early Childhood Research Quarterly in 2022. What is more, schools often use anecdotal evidence to rationalize maintaining uniform policies. One study of more than 6,000 elementary-aged students shows that uniforms do not improve attendance or behavior. This recent national study also found that fifth graders at schools with uniform policies reported a decreased sense of school belonging compared to those at non-uniform schools.

What a kid chooses to wear gives them a source of belonging, according to findings from the Early Childhood Research Quarterly study. Put another way, allowing children to choose how they express and present themselves to the world actually matters. According to the Office of Justice Programs, many larger school districts, such as New York City, have uniform policies put in place with the intent “to improve school safety and discipline.” Uniform regulations also exist in California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia. While Philadelphia public schools maintain uniform policies that were implemented about 25 years ago, the exact rules vary depending on the school. Uniforms in cities like Philadelphia developed in response to school violence and rivalries.

However, much like other cities, the City of Brotherly Love’s elite schools, such as Julia R. Masterman Laboratory and Demonstration School and the Science Leadership Academy, adhere to their own dress codes. While uniform regulations are loosening in some districts, others have adopted more conservative measures.

Take, for example, Jefferson Parish Schools in Louisiana, a public school system where the board passed a new policy requiring skirts to be no more than three inches above the knee. Compare that to the Lafayette Parish School System, which allows skirts to be four inches above the knee. Meanwhile, the East Baton Rouge Parish School System permits skirts up to five inches above the knee. It should be noted that many parents, teachers, and administrators support uniform policies, even strict ones. Those on the pro-uniform side of the debate also claim that uniforms address economic and educational inequities.

This goes against studies that find children enrolled in schools in low-income areas with more students of color have uniform mandates, while higher-income schools with more white students have dress codes that emphasize choice. Studies also find that dress codes disproportionately punish girls, students of color, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. It should be noted that under Title IX, school dress regulations cannot discriminate against a student’s sex or gender. And, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, “dress codes also must be enforced equally,” This means that school regulations on “revealing clothes” such as tank tops cannot only target girls.

In preparation for an expected heat wave that brought triple-digit temperatures to Brooklyn, my daughter’s principal lifted the uniform requirement for the last week of school. If uniforms are not a punishment, why does it feel like a reward to do away with them for a week? The dress-down day came with caveats, as the principal outlined via Remind. She noted:

- Do not overdress your child

- Students may wear knee-length shorts/jumpers/skirts/dresses (make sure they wear shorts under).

- Students are best in a cotton t-shirt (we do not allow spaghetti strap tank tops or tops that show a midriff).

Throughout the year, I tried to recruit other parents to join my anti-uniform movement at my daughter’s school. United we could make change. But I failed to even get one parent to side with me. I assumed other parents also wanted their children to have the freedoms afforded to kids at schools in wealthier neighborhoods. Instead, each one of my attempts to start a united front was met with an awkward silence or polite dismissal.

“What’s with these parochial uniforms?” I whispered to a mother at school dismissal.

“I’m sure they have a uniform policy for a good reason.”

“Then why are all the kids at low-income schools in New York in uniforms, while the rich kids wear jeans to school?”

New York is no different from other cities that allow students at elite schools to choose what they wear. At Brooklyn’s highly-regarded IS 98-Bay Academy middle school, students must simply arrive at school in “clean and neat” attire. At the Brooklyn Science and Engineering Academy, learners need to wear black or khaki bottoms and tops that correspond to their grade level.

This year, the Department of Education eliminated Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives and launched the EndDEI.gov reporting system, rolling back years of work to correct systemic inequities and historical wrongs. Where does that leave the uniform debate to provide greater inclusion and protection to historically marginalized students? It remains to be seen. The ED has nearly outlawed the word inclusion in the name of ending “illegal discrimination” and stopping “wasteful spending.”

Despite federal changes, schools need to focus on creating positive learning environments, not creating new ways to police students and discipline girls who wear spaghetti straps instead of sleeved tops. When schools place unnecessary restrictions on students who already face challenges, what do we expect will happen? Giving students choice in school gives them power. Allowing students to have autonomy over their appearance contributes to a positive learning environment that fosters innovation and successful outcomes.

Before the end of my daughter’s school year, there was a PTA meeting via Zoom. The principal was rushing through her presentation because she was also sitting in the car at her son’s little league game. Even as she hurried the conversation, she could not help offering reminders about uniforms. I started typing in the chat box.

“In the summer of 2024 the New York City Council members passed a bill and a resolution to create a more universal dress code. The Education Department must also report data on dress code policies, violations, and penalties in public schools. What is OUR school going to do to create a more inclusive dress code?” I wrote in the chat box.

“We don’t have dress codes for genders, so we’re already inclusive,” The principal said, after reading my message out loud.

“The bill addresses students of color and LGBTQ+ students who disproportionately get punished because of uniform codes.”

The principal stopped reading my messages out loud. Even so, I posted a link to the bill, hoping others would read it as well. There was no reason to believe I changed anyone’s mind that night about uniforms. Although a few days later came another message over Remind that gave me hope:

Students can now wear black bottoms in addition to navy blue.

Nalea J. Ko: Born and raised in Hawaii, Nalea J. Ko is a journalist turned educator. She is a New York-based special education teacher who is passionate about improving literacy and addressing income inequality in under-served schools. Nalea also earned her MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College.